One of our educational journeys while we were in central Australia was an 8-hour tour of Curtin Springs Station (station=ranch in Australia). In many ways, this was one of the most unexpected and surprising aspects of our stay in the Uluru-Kata Tjuta region, since we had mostly prepared ourselves for the visit to the Aboriginal sacred site. What ensued was a day of exploring another side of the isolation/connection binary that we spent the year reading and ruminating about while at Wooster. It also exposed us to the ranching lifestyle of the Anglo settlers in the region, which closely resembles the cowboy culture of the Southwestern United States. As part of the central frontier, this regional identity occupies a special place in the national imaginary of modern Australia. When asked why they came on the tour, the couple with us answered, “Because we wanted to see the real Australian Outback.”

As we drove away from the hotel region, we quickly realized the expanse of the area. Though we were captivated by the beauty of the landscape, our guide continued to impress on us the sheer distance and isolation of the area from the rest of Australia. We passed a few abandoned vehicles on the sides of the rode, which we were told are left behind by their owners (it is cheaper to buy a new car if yours breaks down out here, rather than to have it towed to the nearest shop). We were also told that the price of food and petrol are much higher in this area than others in Australia. The sheer excess that we experienced in Sydney (wealth, water, food, people) stood in stark contrast to the ways we were experiencing and reimagining physical space and our own spacial relationship to the land and sky in the Outback.

Curtin Springs Station is a one million acre cattle ranch with a population of 30 people (about the size of Rhode Island or Delaware). Throughout the day we kept being reminded of the almost complete isolation of the people who live and work here. The station was leased by the Severin family (Peter and Dawn) in 1956. At that time the area was so remote and unknown that Peter refused to leave the car where his wife could get to it (or even teach her how to drive) out of fear that she would run away. We also learned that schoolchildren went to school by tuning into a classroom on the radio and that wives would create codes so that they could gossip with each other whenever they had the chance to speak over the airwaves. This reminded us that no matter what the distance was between stations, a sense of community, belonging, and support existed for the families that decided to make this their way of life.

Since this is a cattle ranch, we were surprised to hear that people don’t always see cows while on this tour. We saw several, but were shocked to notice that many of them had not been tagged (which means they just roam free and are unaccounted for by the ranch hands). This is because the station controls its cattle though the manipulation of the water sources. We were told that this year was a good rain year and that it meant the cows do not need to obey the water controls. Shockingly, the station has to deal with a 7-10 year rain cycle, which means that there is a good season every 7-10 years (meaning that everything in between is drought). So the planning and development has to operate on a 10 year horizon!

We were continuously reminded, however, that this region of Australia has a semi-arid climate and is not a desert like most people think it is, which accounts for the many different plants and animals that inhabit the area. Nature just became a little ingenious in how it handles those long stretches without water. Here is a photo of the so-called “Halfway Tree.” It is a large Desert Oak that is approximately 400 years old (with Evan standing under it to give a sense of proportion).

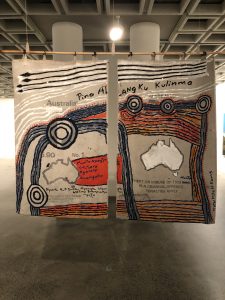

Though this part of the country is isolated, it has also been touched by the forces of globalization. In addition to cattle, which are obviously not native to the continent, the land is occupied by camels. We learned the previous day that there are more than one million feral camels in central Australia. They were brought over when Anglo explorers and their horses failed to survive in the hot and dry climate (and are now exported to Saudi Arabia). Peter and Dawn’s son had the opportunity to study in Europe and brought back knowledge about invitro fertilization, though the station decided to keep doing things the old-fashioned way. And, as we were told time and time again, the current employees of the ranch and the tourist agencies come from all over Australia to escape the cities. In our two days here, we also saw groups and people from Europe, Asia, North America, and Australia. This station has been photographed countless times and its likeness shared on social media for people all over the world to see, which would have been unimaginable for Peter and Dawn when they first ventured out here alone to what they believed was the Australian unknown.

A quick fun fact: many people drive to central Australia, see Mount Conner in the distance and believe it is Uluru, stop and take a picture of it, then turn around to go home (which is why it is known as “Fool-uru”). Here are two pictures of the group: at Lake Swanson (an ancient salt lake that is currently dried up) and in front of Mount Conner. Both are located on Curtin Springs Station (again, it is that big!)

And here is a view of the spectacular sunset at Curtin Springs Station. In many ways, this type of view could only been seen in a vast area of human isolation.

Now that we are in Melbourne, we will get to see a completely different regional identity of Australia. Far from the Outback, we will explore the city that continues its rivalry with Sydney and that claims to have better urban planning, development, and art, food, and culture scenes. We’ve also been told that Melbourne’s “Britishness” is more evident than that of any other Australian city and that they have the best coffee in the country. So as we arrive back to the periphery, with red dust on our shoes, we will continue to look for the images and narratives that connect the urban and rural landscapes and people of this continent.

Jimmy Noriega