Understanding the experience of place!

Yesterday we arrived at Uluru (Ayers Rock) — a place of special spiritual significance to the native people. It’s the connection between land and culture that made this Australia trip especially interesting to me, and the implication that you can’t understand the people without seeing the land. Culture serves to mediate the experience of place for the local aboriginal people: their history and traditions tell them how to understand its meaning and significance. We of the Hales group are having our experience mediated in a different way; tourism, rather than culture, is presenting and packaging the meaning and significance of the place for us. But we are still here. Our bodies are still in this place; we still feel the dry desert air, smell the plants, see the glowing rock. This matters. It not only gives us a deeper and richer experience but also allows us a minuscule window into the experience of others who have been in this place.

Bodily experiences

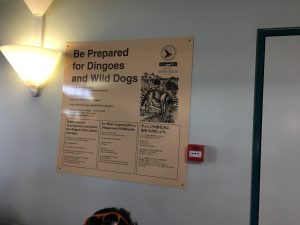

A few days ago we visited the Hyde Park Barracks Museum in Sydney, a building which had housed, first, laboring convicts, and young Irish working women fleeing the Famine. We were invited to lie on the reconstructed hammocks or cots in order to share that bodily experience with those who had been there in earlier centuries (minus the lice, hunger, and floggings). Of course it’s laughably insufficient for a real understanding of what their life was like. We need to avoid the illusion that we can really stand in the shoes of others, especially based on such a brief experience. But it’s a start. I think we need to make the effort to have some point of contact. Shared experiences of place, based on sensory information rather than intellectual exercise, may give us a brief but important opportunity for empathy. As research shows, and technology is beginning to exploit, shared bodily sensations and experiences can help us to understand the perspectives of others. The video in the Ayers Rock airport put it this way: our visit can help us to see the land through Anangu eyes.